A Letter from Samuel Marsden to the editor of the Sydney Gazette 1823

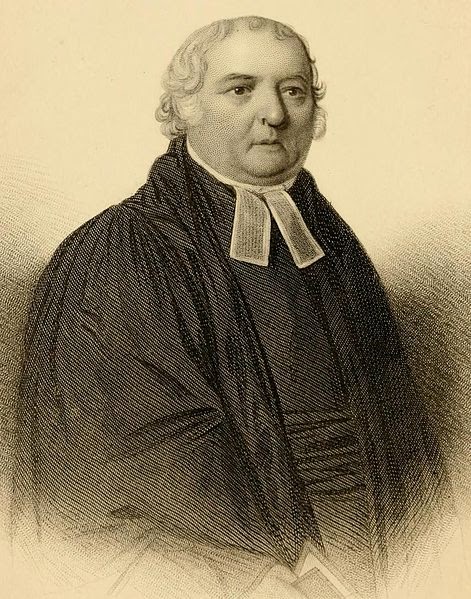

In November of 2014, it will be 200 years since Reverend Samuel Marsden first set foot on the shores of New Zealand in November of 1814. The letter he wrote concerns the Bay of Islands chief Te Pahi who was wrongly accused of being behind the Boyd massacre at Whangaroa in 1809.

Parramatta, 8th Dec. 1823.

SIR,

It may not be uninteresting to some of your Readers who occasionally visit New Zealand, and to others also who are unacquainted with that country, and the character of the inhabitants; and who may, from stress of weather, or other circumstances, be forced to take shelter in some of the harbours on that coast, to learn the original circumstances which led to the first establishment of a Mission to that country, and the benefits that have resulted from that event. I shall, therefore, state some of the facts which came under my own immediate observation. About the year 1805 a chief, named Tippahee (Te Pahi), with some of his friends, were brought to New South Wales in H. M. ship the Buffalo, from Norfolk Island, where they had been left by some whaler. At this period the Government of the Colony was administered by the late Captain KING, of the Royal Navy. On their arrival, and during their stay, His Excellency shewed them the kindest attention, admitted Tipahee to his table, and provided him, and his friends, with suitable lodgings. They were also treated with great kindness by every respectable family in the settlement, whom they visited.

Durrng Tippahee's residence amongst us, I became intimately acquainted with him, and we had many conversations relative to the state of his countrymen. I found Tippahee a man of a very superior understanding, as an uncultivated savage, and capable of receiving any instruction. His companions also manifested strong mental faculties. When they had remained as long as they wished in the Colony, the Governor sent a vessel expressly with them to their own country; so that his kindness towards these savages never ceased until they were safely landed on their own shores, with many presents which they had received from the Crown, and private individuals. These marked attentions made a lasting impression on their minds.

In 1806, Captain KING retired from this Government, and in the beginning of the following year embarked for England. I accompanied him to Europe, and shortly after my arrival in London, I resolved to apply to the Church Missionary Society, and to solicit them to send a Mission to New Zealand, from a full conviction that this noble race of human beings could never rise from their degraded, barbarous state, without the benevolent aid of the civilized world. I addressed a letter to the Secretary, the Rev. JOSIAH PRATT, who introduced me to some of the members. I afterwards submitted my request, or memorial, to the consideration of the Committee, who approved of my application, and passed a resolution to send out two or three mechanics first, when suitable persons could be found, who would venture upon such an apparently dangerous Mission.

In 1809, I embarked again for New South Wales. Messrs. Wm. Hall and John King offered themselves for the New Zealand Mission; and it was determined by the Committee that they should accompany me to the Colony, in order that they might be forwarded to New Zealand. Mr. Kendall offered himself also at that time, but was not accepted then. On my arrival I learned that the Boyd had been cut off in the harbour of Whangarooa (Whangaroa), and burnt; and the master, passengers, and crew massacred and eaten by the natives; and that seven whalers, which were upon the coast at the time the Boyd was cut off, had made an attack upon Tippahee's settlement, in the Bay of Islands, when a number of his people had been killed, and himself severely wounded, These disastrous events seemed to prohibit, for ever, all future attempts to introduce the arts of civilization, and the knowledge of Christianity, amongst such a barbarous nation of cannibals.— Messs. Hall and King retired to Parramatta, and no attempt was made at that time to establish the Mission, though I entertained very strong hopes that the experiment might be tried at some future period. Two or three years after the loss of the Boyd, the Church Missionary Society sent out Mr. Kendall; wishing (if practicable) to begin the Mission. A young chief named Duaterra, a near relation to Tippahee, had lived with me about two years.

He came to London in 1809, and returned with me to New South Wales. At the time Mr. Kendall arrived I had sent Duaterra home to his friends. From my knowledge of Duaterra, and the influence he had with his countrymen,and the anxiety he had expressed for their welfare, I was confident the Missionaries might venture upon their Mission. After Mr. Kendall arrived, I applied to His Excellency Governor MACQUARIE for permission to visit New Zealand for the purpose of establishing the Mission. From the calamities, that had befallen the crew of the Boyd, His Excellency did not feel himself justified in giving me his sanction to go at that period. I then sent Messrs. Hall and Kendall to New Zealand for Duaterra, and some of the chiefs. Duaterra, Shungee, Koro Koro, and Toi, returned with them to New South Wales.

The Governor then gave me permission to visit New Zealand. I took along with me the three Missionaries, Messrs. Kendall, Hall, and King, with their families. We touched at the North Cape, explained to the natives our object, proceeded to visit the inhabitants of Whangarooa, who had cut off the Boyd, and had a long conversation with the chiefs upon that melancholy event, and at last landed the Missionaries at the Bay of Islands, where they have remained for the last nine years.

It must be allowed that the prospect of introducing the arts of civilization, and the knowledge of the Christian Religion, into such a bold, daring, barbarous, warlike nation of cannibals, was not inviting; and that it required some resolution, some self-denial, some sacrifice, to sit down in the midst of such a people, whose habits and customs, and religion, were so revolting to the feelings of civil society.

It is probable the Missionaries might have done more during their nine years' residence in New Zealand, than they have done, to promote the benevolent object of the Society; yet it will be found that very much has been done, when every difficulty connected with their situation is fairly weighed.

Before this Mission was established, the natives of New Zealand were a terror to the civilized world; vessels, even in distress, were justly afraid to put into any of their harbours. Acts of plunder, murder, and other cruelties, were continually committed, either by the natives upon the Europeans, or by the Europeans upon the natives. They were constantly retaliating upon each other.

From the day the Mission was established, to the present time, no acts of cruelty or murder have been committed from the North Cape to the River Thames, a distance of nearly 200 miles, by any of the natives. I explained to every tribe, on my first visit, from the North Cape all along the coast to the River Thames, the object of the Church Missionery Society in sending Missionaries amongst them, and requested the natives not to commit any acts of violence upon the Europeans; and in case the Europeans should treat them ill, Governor MACQUARIE would punish the Europeans when they returned to Port Jackson, for any offences committed by them in New Zealand, as soon as he was acquainted with the nature of their crimes. The natives were satisfied with the promised protection, and have conducted themselves towards the Europeans accordingly. When they were injured by the Europeans afterwards, some of them came to the Colony to prefer their complaints.

I may further observe, since the Mission has been established, and tools of agriculture introduced by the Church Missionary Society amongst them, the cultivation of their lands has increased twenty- fold, as far as the benefits derived from the íntroduction of hoes, spades, axes, &c. have extended. Ships can now, in my opinion, with perfect safety, enter the harbours of Whangarooa, the Bay of Islands, and the River Thames, and procure such supplies of fish, pork, potatoes, and other vegetables, and sometimes poultry, as they may require, unless the crews should commit some act of violence upon the inhabitants.

The natives here also made very considerable advances towards civilization. There needs no greater testimony of this than their conduct towards the crews of the twovessels which were lately wrecked upon their shores;—the Cossack, in the mouth of the River Gambier (Hokianga), on the west side of New Zealand; and the Brampton, in the Bay of Islands. The crew of the Cossack received every attention from the natives that it was in their power to give. After they had lost their vessel, and all their clothes and provisions, they fed them while they remained in their harbour; and, on their departure, conducted the master and crew across the Island to the east side, to the Bay of Islands. I saw several of the crew belonging to the Cossack, who expressed their gratitude to the natives for their kindness and attention to them in their distress.

When the Brampton was wrecked, I was on board. It will be sufficient to shew the favourable disposition of the natives, for me to refer only to the speech of a chief, known to the Europeans by the name of King George, which he addressed to his countrymen, on board the Brampton, after she became a wreck.

From the above facts, it will appear that the establishment of the Mission has, for the last nine years, been attended with the greatest benefit, not only to the New Zealanders, but also to the Europeans; whose vessels, from distress of weather, want of supplies, or other causes, have put into their harbours; where they can now anchor with safety, and obtain wood, water, and such refreshments as they may require.

I should recommend all masters of ships, and their crews, to treat the natives with common civility, and then they need be under little apprehension from them. The fewer natives they admit on board, the less danger there will be of any quarrels taking place between them and the crews of their vessels. Some attention should be paid to the chief of the place, and he should be requested to prevent too many of the natives from entering the ship, lest thefts should be committed by them.

By inserting the above observations in the Gazette, you will much oblige, Sir,

your obedient humble Servant

SAMUEL MARSDEN.

Sourced:

"To the Editor of the Sydney Gazette." The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 - 1842) 11 Dec 1823: 4. Web. 4 Feb 2014

Comments